Economists Will Fail Without THIS

Note: Many readers responded to my last post expressing interest in opening up a community where subscribers could interact. I’ve thrown a poll on my YouTube page to measure interest. Let me know what you think. And while you’re there, see if you’ve missed any recent videos. There’s some good ones!

Let's put your economic thinking to the test. It should be an easy question, but don't be surprised if you fail. I want you to predict the effects of an immigration shock on wheat farming. What would happen to wheat farming if a country stopped accepting immigrants? Or you can flip the question around. How would an inflow of immigrants affect wheat farming?

While you draw your supply and demand curves, I'm going to show you one of my favorite research findings related to wheat. Then we'll get back to the population shocks.

American Wheat Productivity

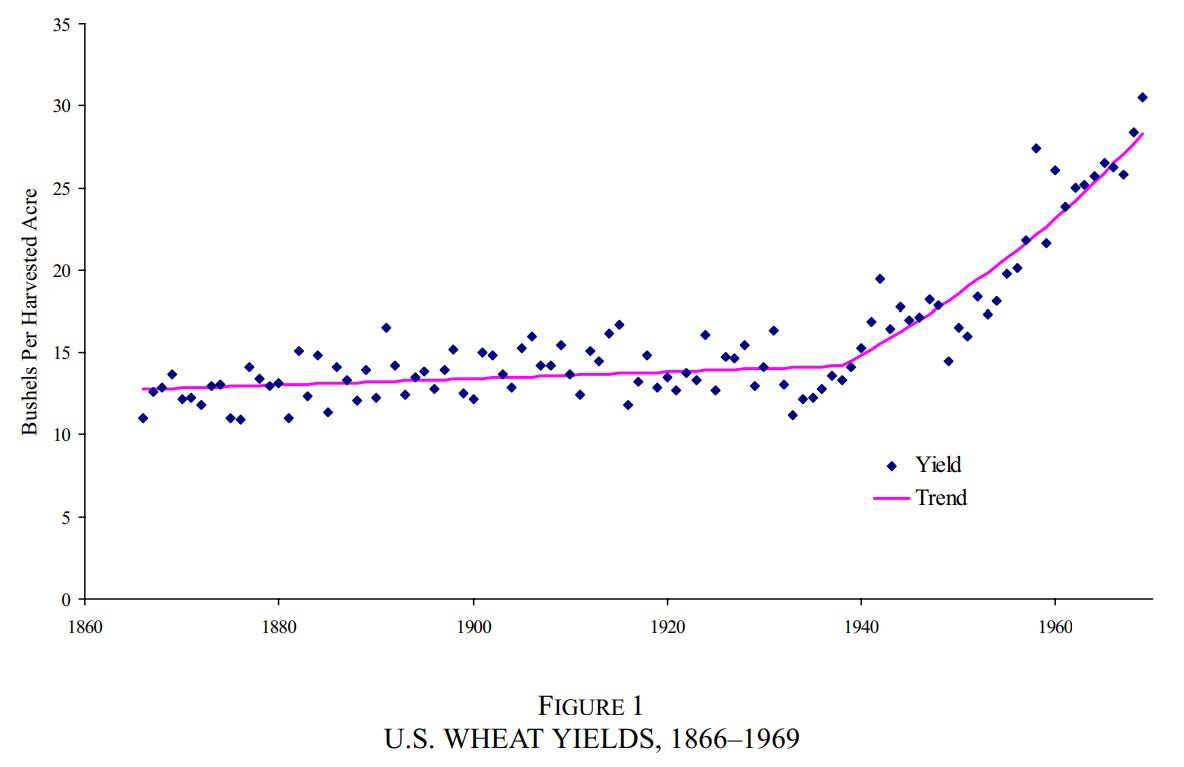

This is a graph of American wheat productivity over a 100 year period. We're measuring productivity using the number of bushels produced per acre harvested. Since a bushel of wheat is a constant measure, if we can pull twice as many bushels from an acre, we've doubled our productivity.

There are two clear trends. For the first 75 years, productivity was flat. Sure, there's a slight positive trend to it, but given the timespan it's pretty flat. Then there's a break and wheat productivity skyrockets. That soaring productivity is an important and interesting time, but I actually want to focus on the flat time.

Why was wheat productivity flat from 1866 to 1940?

Many people saw this trend and concluded that there weren't sufficient biological advances during this period. After the 1940s, Norman Borlaug and the Green Revolution brought high-yield varieties to the world, a major biological breakthrough. But apparently before the 1940s we were stuck in a biological rut.

Or were we?

Two economists, Alan Olmstead and Paul Rhode, saw that flat line and asked a different question: With everything going on during that time, how did that line stay flat?

That's because during these decades wheat farming was like Fievel Mousekewitz and going West. But America is a vast country, and wheat is sensitive to the climate. To a wheat seed, the climates of Nebraska, South Dakota, and Ohio are so different that the same seed could thrive in one and starve in the other. Not to mention that there were fungi in the West attacking wheat (the same fungi that launched Borlaug's research that eventually created the Green Revolution). If nothing was changing, then wheat productivity should have been in steep decline. The fact that it was flat is a miracle!

Olmstead and Rhode took their understanding of the context and explored how wheat survived. They found a robust culture of biological innovation, totally inverting the conventional wisdom.

The key was context. And without it, economists will fail.

Immigration and Wheat

So let's go back to the question at the beginning. What happens to wheat production if population suddenly increases or decreases?

If you said a sudden increase in immigration would increase wheat production, you're right!

But if you said a sudden decrease in immigration would increase wheat production, you're also right!

How do two different population shocks have the same effect on wheat production? It depends on the context.

Back in the 1920s, the United States reversed its immigration policy, moving from effectively open borders to a strong quota system. Closing the border choked off immigration flows to rural areas. As a result, the affected areas switched away from hay and corn, which were labor-intensive crops. When you don't have workers, you rely more on machines, so these farmers switched to a capital-intensive crop: wheat.1

On the other hand, about 25 years later, India had a massive population shift. British India was divided into India and Pakistan, leading to a large population movement. Muslims left India for Pakistan, and Hindus left Pakistan for India. But the Hindus leaving Pakistan had relatively high levels of education, and they were moving to India right at the beginning of the Green Revolution. Although the new seeds promised high yields, using them required an understanding of how to properly adopt cultivation practices to your climate and soil. Since the immigrants had higher education than the natives, areas with more immigrants were quicker to adopt the Green Revolution technologies. Thus, higher wheat production.2

The immigrations effects differed because of the context. In the U.S., immigrants and capital were substitutes. In India, immigrants and capital were complements.

And this brings us to a larger point. I’m worried about economists who make bold predictions without understanding the context. We see it all the time with policy recommendations. We see it when people look at history and try to apply it to the future. And we see it when people try to infer causality from a set of related events.

Economics is rich with models that describe our interactions. Which model is appropriate depends on the context. Without understanding the context, economists will fail to understand the effects of economic shocks.

“The Effects of Immigration on the Economy: Lessons from the 1920s Border Closure” by Ran Abramitzky, Philipp Ager, Leah Platt Boustan, Elior Cohen, and Casper W. Hansen. https://scholar.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/lboustan/files/w26536.pdf

“Displacement and Development: Long-term Impacts of Population Transfer in India” by Prashant Bharadwaj and Rinchan Ali Mirza https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S001449831830175X