It’s Saturday afternoon, and I’m in my home, amazed. My 11 year-old son is sitting in front of me, and he’s reading Japanese. Not Japanese with an English alphabet, like “Konnichiwa.” He’s reading ”それはおいしいです。”

What has me even more shocked is that he only started learning this a month ago.

Well, that’s not completely true. For about a year, I worked with him on Japanese. We would review vocabulary, and sometimes I would give him a Japanese writing assignment. And by assignment, I mean I would print off Pokemon names in Japanese, give him a sheet of symbols, and tell him to decode the names. He learned a few things, but nothing substantial.

Then a month ago I set him up on Duolingo. He does about 15 minutes a day, and his learning has accelerated than inflation.

But the amazing part is that it’s entirely self motivated. He asks to study Japanese every day.

He’s not like this in every subject. He sometimes likes to do his math, but a lot of times we’re pushing him to do it. He absolutely hates doing his language arts work. But for Japanese, he looks forward to it. Sometimes it’s the first thing he does in the day.

Why the difference?

It’s because Duolingo changes the discounting calculation. Let me show you below.

A big thanks to Wayne, JR, Logan, Anthony, and Chris. Not only are they getting exclusive content, they are supporting the newsletter and channel this by upgrading to a paid subscription this last week.

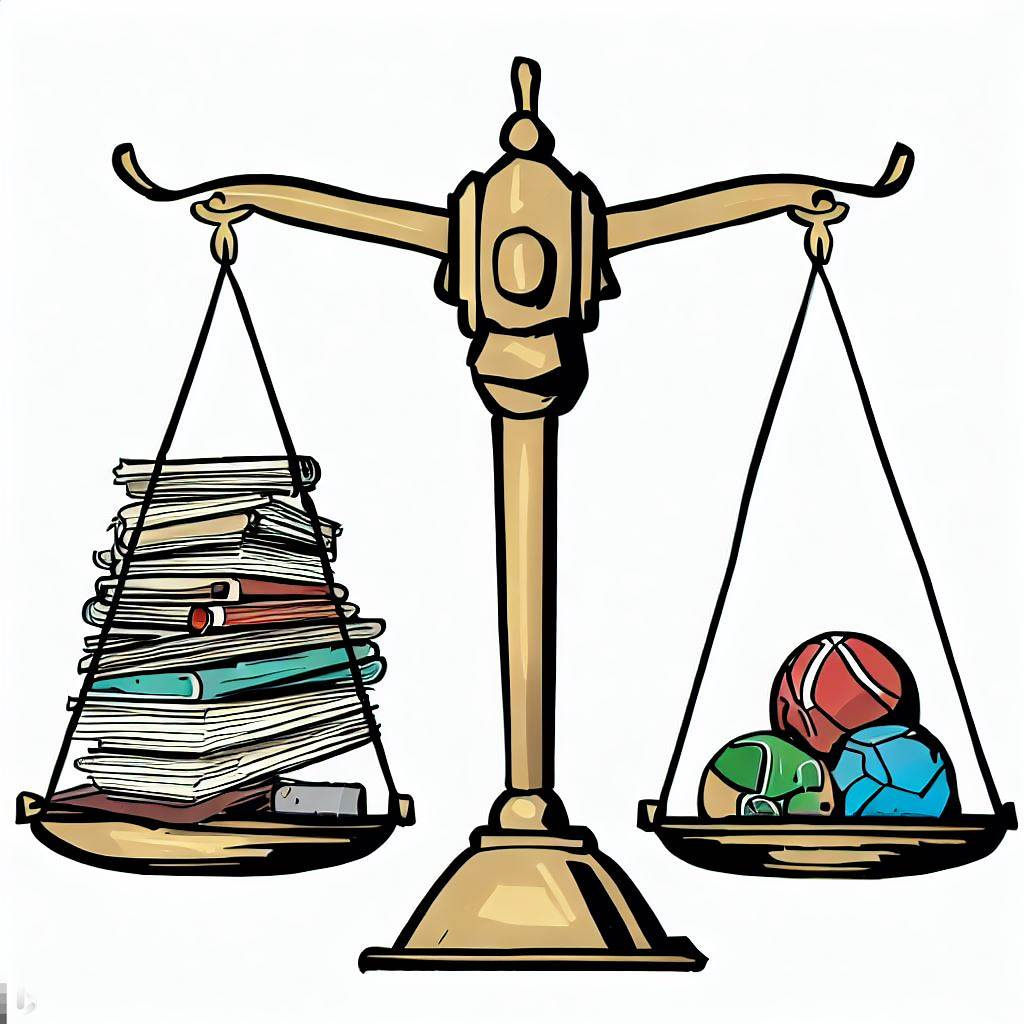

Education is a classic example of deciding between something that bring long-run benefits but short-run costs. Another example is this video I made where Disney was deciding whether to release its content on VHS.

Normally, we look at the costs and benefits and see which ones is bigger. If benefits exceed costs, we do it. But when we compare long-run benefits and short-run costs, we need a way to compare a dollar of costs today to a dollar of benefits in the future.

We do this by introducing the time value of money. We convert future money into present money using a discount rate. If my discount rate is 0.9, that means a $1.00 in one year is only worth $0.90 today. A dollar in two years is worth 0.9^2 * $1.00=$0.81. Any time we take a future value to the present we call it…the present value. (We’re super creative at naming things.)

When someone is deciding to get an education, they look at the present value of the benefits and compare them to the current costs. If the present value exceeds the current costs, you get an education. But this introduces a puzzle: if someone gets an education, then benefits must exceed costs, but then why doesn’t everyone get an education?

One answer is that benefits might differ across people. Another answer is that costs might differ across people. But what I want to focus on with Duolingo is that discount rates might differ across people.

Imagine two people who have the same opportunity to go to college, and once they graduate they’ll get the same job. The only difference between them is their discount rate. One values a dollar in a year as $0.90 today, while the other values it at $0.75. What does this look like in real life? The first person has a higher preference for delayed gratification while the second one has YOLO tattooed on their forearm. How does this affect education? When they calculate the present value of going to school, the first one sees a higher present value than the second, and therefore is more likely to go to school.

The discount rate is a huge reason why kids don’t want to sit down and do schoolwork. Kids heavily discount the future. In fact, kids don’t even understand that there’s a future. So even though adults know that it will benefit them in the long run, kids look at schoolwork and say, “Why do school work when I can have fun right now?”

Duolingo changes that. It doesn’t promise you benefits in the long run. It makes learning fun right now. It uses a carefully calculated rewards system to deliver benefits today and make you crave those benefits tomorrow.

Of course, many companies use these same tactics to get you addicted to their platforms. Social media is built on this dopamine rush.

But what I love to see is how Duolingo proves it can be used to build human capital. It solves a significant issue in education. We’re fortunate to live in a world with tons of educational resources (unless you’re a kid in a poor country, then your schools likely are terrible). The biggest barrier to learning is motivation. And if we could get Duolingos for economics or for calculus, maybe we could grab more low-hanging fruit for making a prosperous world.

And a big welcome to the 29 new subscribers who joined in the last week. Remember, if you refer someone to the newsletter, you’ll be recognized on the leaderboard.

Weekly Trivia

Last week, 44% of you correctly answered that Yale first started admitting women undergraduates in 1969. For me, that is shocking how late it was. I’ll note that Yale did admit women to graduate schools earlier than that. But this piece of trivia is one of the first I cite when discussing how opportunities for women were limited.

This week, we’re continuing the education trend. I’ll provide my source next week, but when was the first PhD in economics conferred in the US?

Links I liked

Very appropriate for this discussion, Dwarkesh Patel interviews Andy Matuschak on how he learns. Andy is a friend, and I have long been interested in how he organizes his notes. In this discussion, Dwarkesh and Andy explore how we can improve the tools we have to learn more.

How Economics Became Yale’s Biggest Major (video)

Last week I posted about trends in undergraduate majors at Yale. I followed it up with a video about why economics is such a popular major. The big lesson to me is that this is not something that only applies to Yale. You can share this with anyone considering majoring in economics.

Stan Lee's Formula For Creating The Perfect Marvel Super Hero

I’m a Marvel fan, so I really enjoyed this story about Stan Lee helping Joe Quesada improve his heroes. It doesn’t have any particular relevance to economics, I just liked it. “Tell us as much about this person as you can, make us care about him, and now when he jumps off that building, our hearts clutch… because we’re inside that costume with him.”

I was recently interviewed by Rasheed Griffith about the political economy of Haiti.

Religion in America using cell phones

Devin Pope, an economist at the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago, is using cell phone location data to look at religious activity in the United States. His findings aren’t profound, but they are super interesting because they provide the most detailed look at attendance that we’ve ever had.

I've always wished I could make economics as engaging for my students as 30 minutes on Duolingo