One of the big questions with immigration and developing countries is whether there is brain drain. This is the idea that opportunities for high-skilled workers is greater in developed countries, so the best and the brightest leave their home countries, which then cripples the country from developing any further.

But some recent papers have caused us to reevaluate that idea.

Roy Story

There’s a basic model around migration that motivates the brain drain hypothesis. It’s so simple, it’s almost trivial. A worker can either stay in his own country or he can migrate. Where he goes depends on how much he gets paid. The novel aspect of this model is that countries have different demand for skilled and unskilled workers, so one country tends to attract skilled workers while the other attracts the unskilled. This is called the Roy Model.

Let’s focus just on the market for high-skilled labor. We’ll begin with a standard supply and demand graph, showing there is an equilibrium number of workers (Q*) in the high-skilled profession.

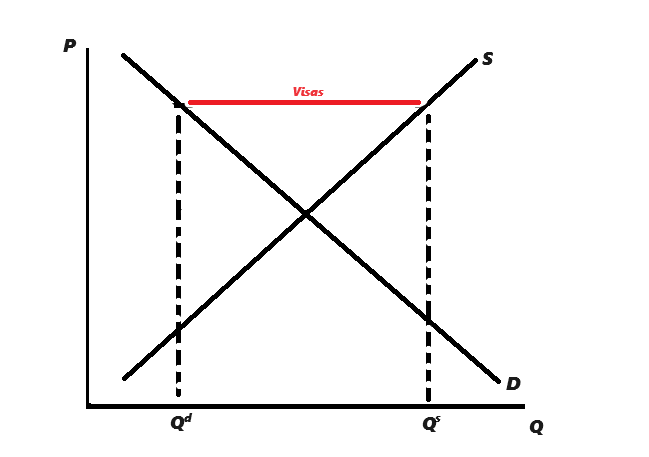

Now let’s open this country up to migration. And let’s say that the world price for this profession is higher than the domestic price. What we get is the graph below. That high world price induces a lot more workers to move into this profession, bringing the supply of workers out to Qs. But now local consumers have to pay the world price for the labor (otherwise the worker would just move to the country where his services are in higher demand), so demand falls to Qd<Qs. Since the local demand isn’t high enough to employ all of the workers, we see all workers above Qd migrate (marked by the red line).

To the country, this looks like brain drain. First, you lose a share of your local workers, as marked in purple. So you actually have fewer lawyers, doctors, and programmers than you did before. But the global demand has led to a bunch more people becoming lawyers, doctors, and programmers, and you see them fleeing your country. Even though those professionals wouldn’t have chosen those careers without the global market, they still represent the workers with high enough skills to be on the margin of choosing that profession and the next best alternative. You’re losing a lot of skilled workers!

In the strictest interpretation of the graph, this is totally fine. Obviously this is great for the world because there are more high-skill workers, and it’s great for those migrants because they are getting paid a lot more. Yes, the country has to pay more for professional services and, as a result, consumes less. But the loss in consumer surplus is overcome by the much larger increase in producer surplus.

But in a dynamic sense, this can be worrying. Endogenous growth theory says that a major contributor to growth is human capital externalities. Education is not valuable just for its labor market returns. As a country gets more educated people, those high-skill workers interact and figure out the ideas, plans, and technologies needed to grow the economy. You get miracles like the University of Utah’s graduate Computer Science program in the 1970s, which created Ed Catmull (Pixar), Alan Kay (object-oriented programming), James Clark (Netscape), and John Warnock (Adobe). But if all of your educated workers are leaving for another country, you can’t get these interactions, and your country can’t grow.

There’s a similar phenomenon that someone conjectured about Haiti (my area of interest). From 1957 to 1986, the Duvaliers ran a dynastic dictatorship. Given Haiti’s history, it was surprising that the government could be both stable and repressive. Where was the resistance? Some believe it was because this was a time of high labor demand in the Dominican Republic, and those who were most able to resist decided instead to take high-paying jobs on the other side of the island. In fact, this argument is still made about the situation in Haiti today.

In summary, the brain drain hypothesis says that high-skill workers leave the country, chasing higher returns, and the country of origin is left in a poverty trap.

But what does the recent research say?

Brain Gains

Two recent papers have looked at episodes of high-skill migration to the US.

The first looks at opportunities for nurses. In 2000, the US, facing a shortage of medical workers, decided to increase the number of visas available for foreign-trained nurses. A big source of immigrant nurses was the Philippines.

The second looks at IT workers in India. With the rapidly growing IT-sector in the US during the 1990s and 2000s, the US began opening immigration to tech workers. A big source of immigrant tech workers was India.

Since both are dealing with an expansion in visas, let’s revisit the graphs and look at the fine distinction.

Below is the market for high-skill workers when migration is regulated with visas. Note that it looks the same as the migration graph above (because they are literally the same base), but that instead of using a world price, I have a quota of visas. But these visas produce the same results as a world price: you still get migrants leaving the country to take advantage of the higher wages abroad.

But there is a key difference between visas and prices. What happens when the supply curve shifts under world prices? Well, assuming the country is too small to affect those prices, you just get more migrants leaving the country. But with visas, that won’t happen. The number of migrants is fixed. So if you shift the supply curve, you’ll get more professionals, but not all of them can leave. Instead, you get more of those professionals at homes. The new ones that stay have been marked in blue below.

That means visas create an opportunity for brain gain. Instead of losing your professionals to a global market, you can retain some in the country. The key ingredients are (a) visas that restrict migration and (b) a shift in the supply curve.

How would the supply curve shift? Colleges could expand degrees in those professional categories and train more lawyers, doctors, and programmers. And there’s probably going to be demand for those programs since there’s an opportunity to get higher wages.

But what happened with nurses in the Philippines and IT workers in India? In both cases, the expansion of visas led to more nurses and IT workers in their respective countries. What appears to be the mechanism behind the gain? Both countries rapidly expanded educational training. For example, in the Philippines, enrollment in nursing programs tripled, leading colleges to open new programs at their schools.

I love these papers because of the implications for education in developing countries. The decision to go to school is based off the expected costs and benefits of education. These papers show that people respond to an increase in expected benefits and that, under the current world migration model, those gains are not all lost to other countries.