Note: I know it has been a while since my last newsletter! When school started, I got out of routine. The good news is I have posted a few videos since that last newsletter, so go find Market Power on YouTube and you can see them.

Addressing education in developing countries is a major policy priority. Since human capital accounts for about 30% of the difference between rich and poor countries, improving education can have a significant effect on pulling countries out of poverty. Even better, about 65% of the difference comes from differences in productivity, and a more educated population could make significant gains in productivity. So there is an easy case that we should be working to improve education around the world.

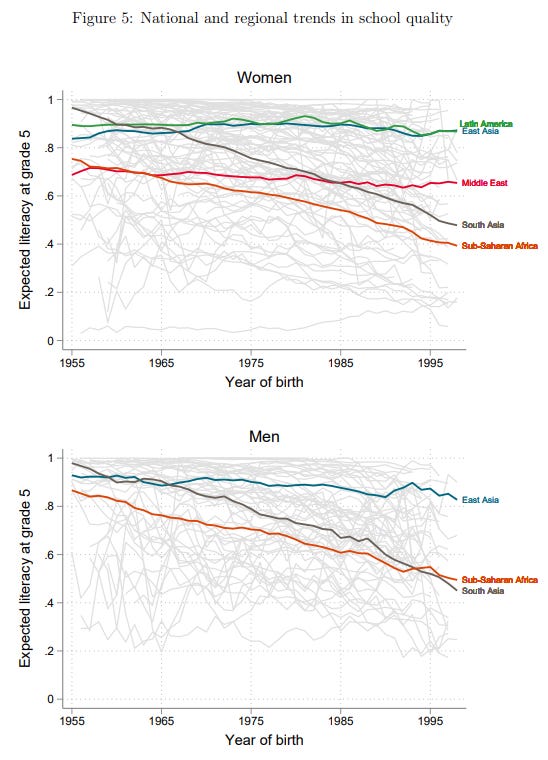

But there is a problem with interpreting this priority as, "We should increase schooling." The last 50 years of development policy saw a relentless focus on getting kids in school. At the same time, school quality has fallen steeply. For example, in Haiti the literacy rate for men who had completed five years of school in 1954 was 92%. By 1996, it had fallen to 73%. The biggest declines in school quality have occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where today the literacy rate at grade five is around 55%.

This isn't surprising when you consider how schools in these countries function. A lot of these countries setup their school systems while still a colony of a global power. The purpose of a school back then was to train the next generation of colonial bureaucrats. So the schools were in the empire's language, even if most of the population didn't speak it. This wasn't a huge impediment then, since most of the students were part of the local elite and learned the language anyway. Over the decades, more students were pushed into school, but the language didn't change, so the majority of students didn't even understand the curriculum. This is why giving schools free textbooks had no effect on student outcomes: textbooks don't help when no one can read them.

But that doesn't mean education in developing countries is hopeless. In fact, there is an educational intervention that was so powerful it made me believe that we could not only close the education gap in poor countries, it wouldn't be that difficult. Unfortunately, the same intervention proves that it almost certainly won't work at all.

The Insanely Successful Intervention

Since I want you to appreciate what this intervention does, I'm going to start with the results. But for you to truly appreciate what the results mean, I'm going to briefly show you the results from another intervention.

Back in the late 1990s, Colombia started offering a school voucher program. It gave students the funds to attend school, and the voucher could be renewed if the student passed their end of year exams (think of it like a merit-based scholarship). The program's effectiveness was evaluated by a superstar team of three economists. I say superstar because two of the economists would go on to win Nobel prizes and the third graduated from my alma mater (BYU). They found that the vouchers increased graduation rates by 5-7 percentage points and that average scores on college admissions exams increased by about 20% of a standard deviation.

I want to focus on that increase in test scores. A 20% increase in test scores sounds huge, but when we look at the distributions of test scores for those who got vouchers and those who did not, the visual evidence is underwhelming. The distributions look almost exactly the same, but the vouchers are shifted just a bit to the right.

Now, I'm not going to spurn an increase in education. But this doesn't look transformative. Unfortunately, this is better than what most interventions look like. The median education intervention increases learning by 0.1 standard deviations.

With that context, let me show you the distributions for this insanely successful intervention compared to the control group.

Those are two completely different distributions. This figure is indicative of transformative change: everyone in the control group fails the exam while nearly everyone in the intervention passes.

What did they do?

This graph comes from a study published last year in the Journal of Public Economics called Large learning gains in pockets of extreme poverty: Experimental evidence from Guinea Bissau. The intervention is an ambitious effort by academics in an environment that was hostile to education.

What did education in rural Guinea Bissau look like? First, teachers did not show up for classes. Strikes disrupted 25% of school days. Even when there was no strike, teachers were frequently absent without substitutes. Furthermore, school was in Portuguese, which none of the students use as their native language.

So the research team saw some easy interventions and started their own schools. First, they trained and monitored teachers to make sure they were competent and present. Second, they opened a Portuguese preschool, giving the students an extra year of language training to make sure they understood the material when school started. While there were a few other details to the intervention (like smaller class sizes), I think these are the two most important and contribute to the huge change we see above. Those results are from testing after grade 3.

What does a student look like after attending one of these schools instead of the standard option? If you went to these schools, you could at least recognize one letter in the alphabet. While this seems like a minor achievement, 35% of students in regular schools couldn't identify a single letter in the alphabet. On the reading comprehension exam, the average score in the intervention was 72% while in the control schools it was 1% (96% scored 0).

On the one hand, this result shouldn't be too surprising. Schools are in Portuguese because they prepared students to work in the Portuguese bureaucracy. Since most students don't speak Portuguese, of course they aren't going to learn. On the other hand, this is shocking because this seems like such low-hanging fruit. Make sure students speak the language and their teachers are in school and you can get transformative education.

As much as I love these results and wish the intervention would be implemented around the developing world, I'm not advocating for it. Unfortunately, I think this intervention would be a massive failure at scale.

Why this will fail

My reaction seems overly negative. Plenty of countries manage to get their teachers to come to school and teach in a language the students understand. Surely this is possible to do at scale.

A great example of why I'm not optimistic for the intervention comes from the study itself.

Initially, we recruited a group of nearly 50 prospective ‘untrained’ teachers to deliver the intervention and trained them for one year. At the end of this year of training, the trainees reneged on their commitments to us, demanding a dramatic change in the agreed-upon employment conditions – including a salary increase to a level equivalent to that of the education ministry’s director-general – and sued us in the country’s courts. While the government sided with us and these individuals’ suit was determined to be without merit, we were forced to postpone the study until the court case was resolved. The case was ultimately resolved in our favor, but resulted in our loss of all 48 selected candidates.

This resolves the biggest puzzle around this paper. The intervention is not proposing something radical. The intervention was an obvious solution to a problem I bet everyone inside the government knows exists. If that's all it took, they could resolve it in years.

But in reality, there is a deeper political problem. Either the state lacks the capacity to implement such a change, or the general populace lacks the political clout to force a change. The political equilibrium is perverse, and without major changes it will never reform the school system.

What's my most optimistic take? If the government abdicated responsibility over administering education and gave it to non-profits. But this creates an entirely different political problem, so I don't see it as a feasible solution.

As excited as I am about results like this, it furthers my belief that the more serious issues in these countries are political economy problems.

Hmm... I'm not sure what you are claiming the greatest education intervention is. Surprisingly, removing absenteeism is not, in fact, what the literature ranks as the strongest education intervention. In the big meta-analyses of Rachel Glennerster[1] and the RCTs of Duflo[2], the best bang for buck in classroom learning is tracking and ability grouping, outflanking teacher absenteeism, class size, and teacher training by quite a margin.

But you know how it is. Government capacity to make or even allow good interventions to occur is often weak. But almost all developing countries have a private school system, and those systems do frequently and reliably can outperform the government system as you say[3]! But is ability grouping likely to fail? I don't think so. You only need the administrators and teachers at the school to get on board. That seems to be a job which NGOs could do successfully, without stepping on any government toes or regulations.

[1]https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.101.5.1739

[2]https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34658/How-to-Improve-Education-Outcomes-Most-Efficiently-A-Comparison-of-150-Interventions-Using-the-New-Learning-Adjusted-Years-of-Schooling-Metric.pdf

[3] https://econjwatch.org/articles/big-questions-and-poor-economics-banerjee-and-duflo-on-schooling-in-developing-countries