Today’s video reminds me of getting choked. And that lesson will hopefully help you in your personal pursuits.

Three months ago I started learning Brazilian Jiu Jitsu (BJJ). I have been interested in it for years, and now that I was vaccinated I wanted to get out and try something new. I show up for class unannounced and they welcome me to class. Fifteen minutes later, my face is buried in a guy’s stomach and his legs are wrapped around my neck. In these three months the move I have mastered is that tap out: that is, me tapping the mat to let my opponent know I can’t breathe.

The goal for today’s video is not to make you tap out of Market Power.

Today’s video reminds me of BJJ because it’s a product of feedback loops. Feedback loops are a process where you try a hypothesis, see it fail or succeed, and adjust based on the results. BJJ gives great feedback loops. If you try a move and find your opponent’s legs around your neck, you know you need to do something different. That first month I never won a sparring match. But I learned what worked for me and how others exploited my weaknesses. Now I still lose a lot, but I win about one out of every five matches.

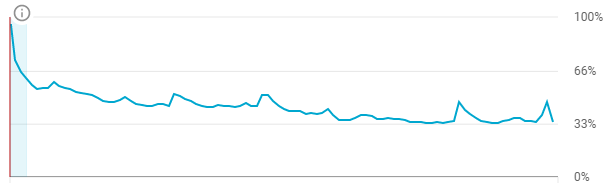

Similarly, YouTube provides great feedback loops. For every video, I know exactly how many people watch each second. Here’s an example below. Within the first 30 seconds of this video, 40% of the people who started the video had already left. Throughout the video you can see moments where there are spikes in viewership: these are moments in the video that viewers care about, so they skipped to those parts.

This graph is data-based feedback on how I’m doing on YouTube. It tells me I need to make my hook more interesting so I don’t lose so many people in the first 30 seconds. It tells me I need to add more value throughout the video, not just in certain moments.

So why should you care about YouTube videos or BJJ? Because you also need feedback loops. No matter what you’re pursuing, you should be testing hypotheses, seeing the results, and then adjusting your approach. If you want to become a better economist, you need to know what’s holding you back.

The problem is that feedback loops are sometimes hard to find. As a research economist, this is where I get frustrated with the profession. Feedback loops can take years to complete. It can be difficult to improve when you don’t learn your mistakes until they’re past correction.

I wish I had an answer on how to make feedback loops when they aren’t immediately available. How do you get feedback when it’s not naturally available?

The Economics of Harry Potter World

I mentioned last week that I was going on vacation. I surprised my daughter with a trip to Orlando, Florida and we went to the Wizarding World of Harry Potter. Of course, as I was there I could see economics all around me, and I had to make a video.

How did feedback loops affect today’s video? First, it’s one of my shortest ever at 4 minutes and 57 seconds. Second, hopefully you feel a different energy. The goal of both changes is to deliver value throughout the whole video.

So if you want to see what I learned, head on over to the channel and enjoy the show!

Future

a16z, a Silicon Valley venture capital firm that has backed some of the world’s biggest startups, started a new publication this week called Future. It looks like their vision is to focus on how tech and tech-adjacent approaches can create positive world change. I enjoyed this piece on funding research to fight COVID by economist Tyler Cowen (writer at Marginal Revolution and backer of Market Power). I haven’t read this one yet, but as I was browsing the website I saw this article on choosing the metrics that will guide your business decisions, which looks interesting based on today’s focus on feedback loops.

It’s only been open for the last week, but it piqued my interest enough to subscribe.