"Is it better for a student to get an A in a regular class or a B in an AP class?"

It's my senior year of high school and I'm reading the Frequently Asked Questions page of Harvard's admissions website when I come across this question. It's a very economics question. What's the trade-off between grades in regular classes and AP classes? (AP classes are college-level classes for students in high school.) At the heart of the question is a risk-reward trade-off. Do you take the easy A or take the harder class with your GPA at risk?

I was reminded of this question the other day when I got an email from a student asking about his grad school applications. He's in a Differential Equations class, but the semester has been tough. He wanted to know if a B would ruin his applications.

Maybe he had been reading this admissions page, which had some unfortunate news. "Is it better for a student to get an A in a regular class or a B in an AP class?" Harvard answered, "We usually look for students who can get an A in an AP class." Brutal.

Over 15 years later, and I can still remember the answer. I think it stuck because it struck at an error in the question. The type of student who goes to Harvard is the type of student who doesn't have to ask that question.

The question about math grades also has an error, but it's different.

When we worry about grades on our applications, we worry about the signals we are sending to graduate schools. Does this grade show that I'm smart enough to succeed? I had the same worries when I was an undergraduate. I had read that Topology was a class that sent good signals, so I took it. And I will always remember the first day of that class.

I'm sitting in the middle of the classroom when this frail old man shuffles into the room looking like Professor Binns, the ghost who teaches History of Magic at Hogwarts. He passes out a sheet of paper with some theorems, then asks in a whisper, "Who can prove the first theorem on the board for us?" I haven't even finished reading it when half of the class raises their hand. A student walks to the front and quickly proves it. "Who can do the second?" Again, the hands rise before I have even processed anything. But I was catching on, and I jumped ahead to Theorem 6 to see if I could figure it out by the time we reached it. I couldn't. At the end of the semester, I worried about whether my grade would help or hurt my applications.

But why are we so focused on the signaling aspect? There's a human capital side too. If you're traveling to France, would you rather have a companion who got a B in French or one who had no exposure to French at all? A B in French is far from fluency, but at least it means your companion recognizes some vocabulary and is aware of basic grammar. A B in Differential Equations means you struggle with some solution concepts, but at least you recognize the material and where you struggle.

Because here's my secret: I never took Differential Equations. There were times in graduate school (namely, my macroeconomics class) when I didn't understand the material because I had no exposure to differential equations. In those moments, I would have been grateful for that B because it meant I knew something, rather than nothing.

Our focus on grades interferes with developing our human capital. Eventually you get the freedom to learn at your own pace, make mistakes, and experiment with new fields. But it is awful that during the time when most people are investing in their education, we have designed incentives to reward the signal but not the skill.

Video Coming Friday

I am participating in a super-secret YouTube collaboration (well…not that secret). As part of it, I’ll be releasing a video this Friday. Be on the lookout!

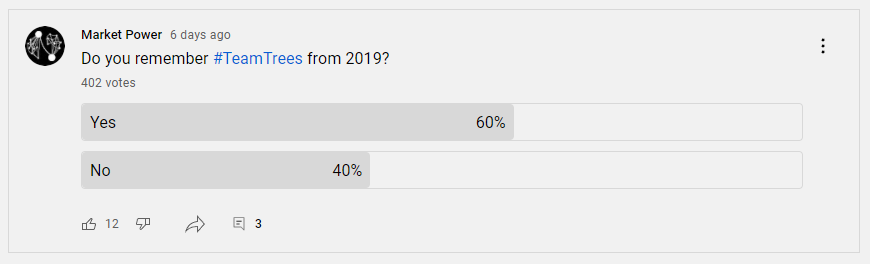

In a totally unrelated vein, 60% of you said you remember #TeamTrees from 2019.