Is there anything today that could not have been invented 1,000 years ago? I used to think not, but I’ve recently changed my mind.

One of my favorite quotes on economic growth comes from Paul Romer, who won a Nobel Prize for his contribution to growth theory. He begins his seminal paper, Endogenous Technological Change, with this:

The raw materials that we use have not changed, but as a result of trial and error, experimentation, refinement, and scientific investigation, the instructions that we follow for combining raw materials have become vastly more sophisticated. One hundred years ago, all we could do to get visual stimulation from iron oxide was to use it as a pigment. Now we put it on plastic tape and use it to make videocassette recordings.

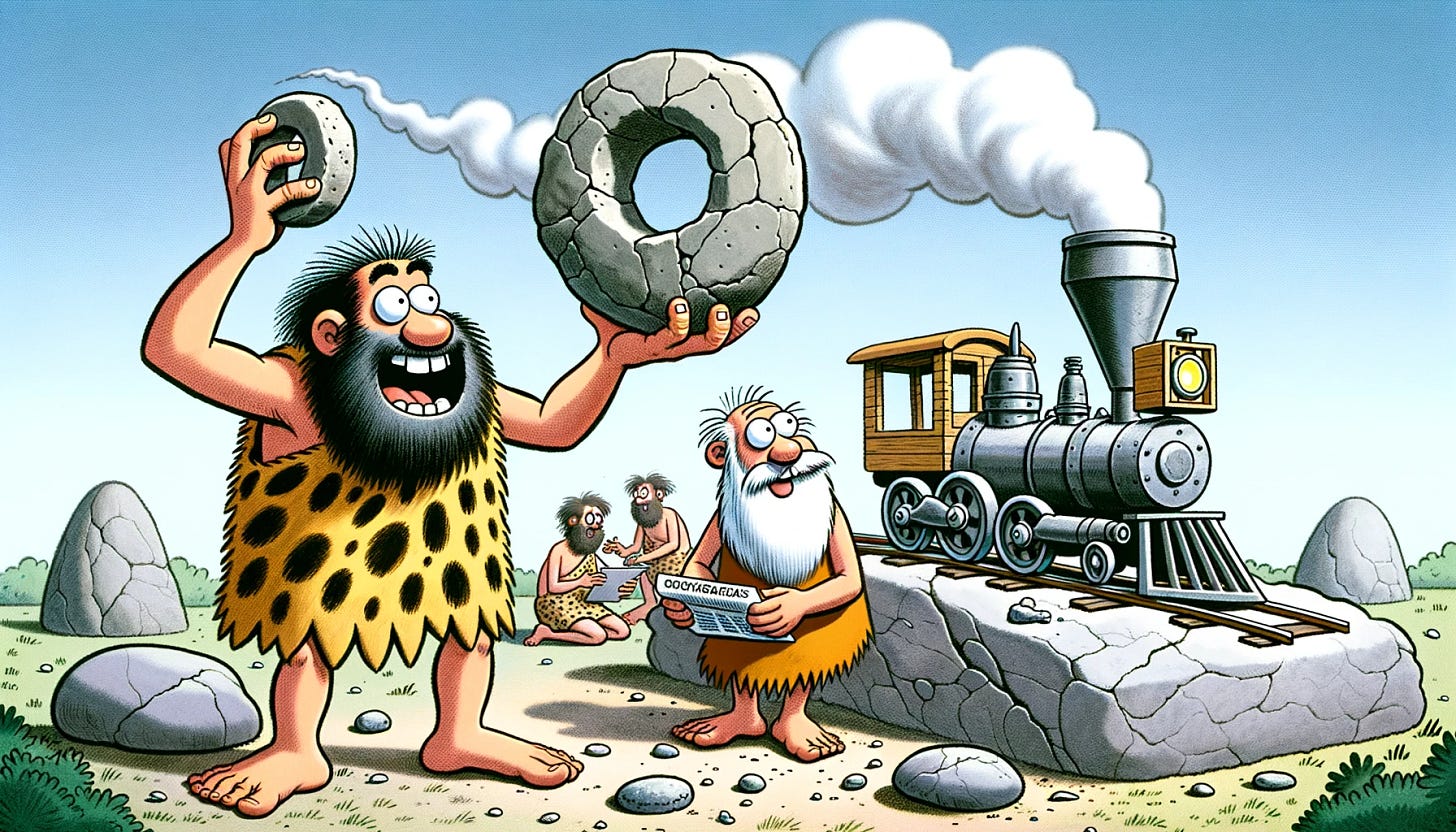

The way I explain this to my students is to say that every technology we have today could have existed 1,000 years ago. There was no asteroid that hit earth, gifting us rare resources that created a technological turning point. The key to progress has been ideas. Recipes. Instructions.

“Let the steam condense in a separate container,” was a recipe that helped create the Industrial Revolution.

“Combine a variety of wheat that is top heavy with a variety that has a thicker, shorter stock,” was the recipe for the Green Revolution.

“Use specific combinations of 0s and 1s to represent data,” was a recipe that led to the Computing Revolution.

What’s interesting about all of those recipes is that they could have been implemented earlier. If you knew how a steam engine worked, you could go back in time and “invent” it, hastening the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, there were several people who almost invented the steam engine long before the 1800s. There were not many technological constraints, just an idea constraint.

Sure, there are some technologies that build on each other. You can’t leap to microchips without inventing a slew of other technologies that form the foundation. But if you had The Modern Technology Cookbook, with all of the designs and instructions for how to make those technologies, you could get pretty far.

Yet, I think we’re seeing the birth of a technology that is unique to our century. Something that if we went back 1,000 years, we would still have to wait 1,000 years to invent it.

And that’s generative AI. A program like ChatGPT.

That’s because the raw materials for ChatGPT aren’t metals, mortar, or minerals. The raw material that that built ChatGPT were messages, musings, and monographs. ChatGPT was trained on writings. Writings compiled over hundreds of years across millions of people. If we travel back 1,000 years, we can find petroleum, lithium, and silicon. But we can’t find Pascal, Leibniz, or Shakespeare.

Of course, someone could object and say that ChatGPT is just a list of billions of numbers. If you bring those back, you have it. Sure. And if you bring any other invention back in time, you have it to. The difference is that with other inventions we bring back, you might be able to reverse engineer it. You could study it to understand the mechanics and learn the science. But a list of 200 billion numbers reveals nothing and would do nothing to advance science.

Besides the insight that this is a unique characteristic of generative AI, this insight reinforces the ideas from endogenous growth theory, which began with the paper I cited in the intro. Economic growth comes from ideas. And those ideas are not just recipes for combining materials. They have become materials themselves.

Links I Liked

Marc Andreesen, who basically invented the internet, has written a manifesto on technology. He cites tons of economics concepts. If you’re interested in hearing about his writing process, check out his interview with David Perell.

(nearly) Free book on Development Economics

I don’t know what’s wrong with Amazon’s pricing algorithm, but Gambling on Development is only $2. That is basically free, especially for how great this book is. Buy it before Amazon realizes what happened.

Transaction Costs in Delivering Aid

A lot of my research focuses on the role of transaction costs in creating inefficiencies in markets. This article struck me because the conflict in Haiti is create transaction costs in delivering aid. Haiti’s capital is overrun by gang wars, and since the war is developing and decentralized, there are not only multiple parties to negotiate with, the parties change frequently.

My course on applying for graduate school is hosting a live Q&A on Oct 28. If you enroll before then, you have a chance to submit questions and participate in the livestream.

The last thing I need is more economics books, this is as good excuse as any to buy more though.

Professor Palsson, thanks for a fascinating article.

I do think that you could create something (at least almost) as powerful as ChatGPT in 1000 AD, though. If my understanding of Textbooks Are All You Need (https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.11644) is correct, you need only about 7 billion tokens (~4.5 billion 6-letter words) of textbook-quality data to create a powerful LLM. If the average textbook has 100,000 6-letter words, that's 45,000 textbooks. That's the output of ~100,000 trained professionals working for 1-3 years.

If the results from the above paper generalize, a lot less than the total number of poets in human history could generate enough training data to create a decent poetry-writing LLM.

You can generate text from these less-powerful-than-ChatGPT LLMs to create training data for a more powerful LLM, your 1000 AD ChatGPT.

You could object that you'd need an army of professionals to invent a 1000 AD LLM, but I'd counter that you'd need such an army to build any complex invention: semiconductor fabs, the Internet, etc. In fact, most of these latter inventions would require more than ~100,000 trained professionals, I think.

Also note that time can make up for a lack of training data. GPT-4 is much more powerful than ChatGPT, even though both were trained on basically the same data, because GPT-4 is more cleverly engineered.