Do Refugees Get Smarter?

I am researching refugee camps, and I’ve come across a finding that is so interesting I wanted to share it. The claim is that refugees and their descendants place a higher value on education than non-refugees.

Let’s examine the argument.

The Model

Imagine you have two ways of increasing your future income. First, you could save your money and get a return on that savings. Maybe you own some land and have an opportunity to improve or expand it so you can farm more food. Or maybe you buy a cow that produces milk for you next year. Second, you could get more education. The next year you work smarter not harder and earn more, and your income is higher.

Of course, in some ways, these are the same thing. In both, you're sacrificing current consumption for higher consumption in the future. For the saving, you're working hours today but don't spend that money today. For education, you don't work those hours today, but instead you use those hours for school. There's a trade-off: every hour you spend in school is an hour you are not making money to either consume today or save for tomorrow.

But if you're a refugee, there's an important difference between them. If your savings are in your land or livestock, it is difficult or impossible to take that with you when you're fleeing conflict. You might have a shot with livestock, but it's impossible to take your land to another country. On the other hand, education is always with you. Even if everything you own is stripped from you, you will still have your education.

Now imagine you're a refugee. You're considering the way to build a better future for you and your family. Do you think land is the key? Probably not. What if you are forced to flee again? All of that work will be lost. So what do you do instead? You look at investing in human capital.

Brenner and Kiefer hypothesize that forced migrants and refugees will perceive a higher probability of losing their immobile property, thus they will invest more in education. They put forth some suggestive evidence, but they admit it wasn't a convincing case.

Other papers, however, have started to examine this hypothesis further.

Empirical Evidence

The biggest tests of this hypothesis are all associated with World War II. This is not surprising because (1) the war displaced a lot of people in Europe and (2) Europe has good data we can analyze.

One test looked at Germans who were forced out of Eastern Europe. As they integrated into the economy, many ended up in jobs with lower incomes. The exception was displaced farmers, who left agriculture and shifted to industry. Among the result in the paper, the economists show that descendants of the forced migrants might have had higher education than comparable Germans. The effect is not super strong, but it is consistent with the theory.

A stronger test looks at the other side of the border. After World War II, the USSR took the Eastern portion of Poland, and Poland's Western border expanded into Germany. The Poles living in the East moved to the West. In 2015, the descendants of the forced migrants had higher levels of education than other Poles. More interestingly, the descendants answered on a survey that they thought material goods were less important to a successful life, indicating the history of displacement shifted their preferences.

The ability to invest in education, however, might be limited by opportunity. In my own work, I look at Haitians forced out of the Dominican Republic. I show that their descendants have lower literacy rates. Why aren't they investing in education? I show that they have less access to educational opportunity, specifically they are much less likely to have access to adult literacy centers.

So there is some evidence for the hypothesis. But I'm not 100% convinced by the model.

Religious Implications

I'll get to my biggest objection, but first I want to address an interesting religious connection I found. If that's not what you're interested in, just skip to the next section.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a history of displacement. It began in 1830 in New York, but soon thereafter the center of the Church was in Ohio. A large community moved to Missouri, but they were forced from their homes and moved to Illinois. After the assassination of Joseph Smith, the Church and its members moved across the West and settled in Utah, where I now teach.

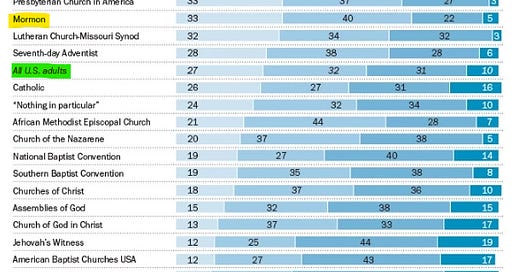

What's also interesting is that the Church emphasizes the importance of education. Members of the Church are more likely to get a college degree than the average adult, and they are much more likely to get some college education.

But what I find the most interesting is that there is doctrine within the Church on the importance of education. Read the following verse of scripture and think about the model I outlined above:

"Whatever principle of intelligence we attain unto in this life, it will rise with us in the resurrection. And if a person gains more knowledge and intelligence in this life through his diligence and obedience than another, he will have so much the advantage in the world to come."

Is it a coincidence that a religion that experienced forced displacement in its early history also teaches that education is one of the only things we can take with us into the next life?

My Concern

I like the model and I think there is some good evidence that refugees care more about education. But here's my problem. There is nothing in this model that is exclusive to refugees. It says that if there's a threat to my property, I should invest more in education. But lots of poor countries have poor property rights and also low education rates.

Maybe this is like the case of Haiti I mentioned above. Maybe they would be investing in education if there was more opportunity. But it's important when putting forth economic theories that we consider all of the implications.