Over the weekend, we celebrated Easter. As we did, I wondered if Easter is the most economic holiday.

Think about the economic language used to describe the mission of Jesus Christ. Our sins and shortcomings are often seen as debt, and “the wages of sin is death.” He gave his life as “ransom for many” and “paid the price for our sins.”

This isn’t the only place where we see economic language appear in a different context. Take biology. “Although Darwin had no formal training in economics, he studied the works of early economists carefully, and the plants and animals that were his focus were embroiled in competitive struggles much like the ones we see in the marketplace.”

It’s easy to say that the world is governed by biology or physics, but these forces work at such a level that they are nearly invisible without the right tools. That’s why most of our advances in these fields didn’t happen until the last two centuries. But economics is in front of us every day. We constantly face trade-offs, exchange with others, and engage in production and consumption. So the language of economics tends to describe hidden areas of knowledge, like biology or physics. Or religion.

Economics is transcendental.

The Future of NFTs

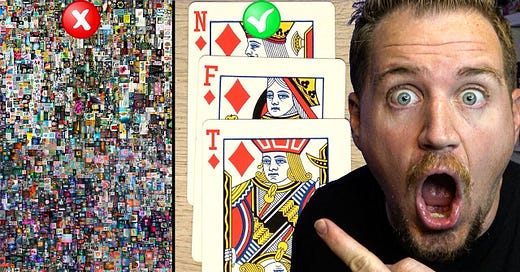

I’ve been thinking more about the future of NFTs. Here’s my hot take: NFTs in art are a red herring.

The art market has always been weird, so NFTs have found a great niche where they can gain attention. But because of that, people are getting the wrong impression of the future of NFTs.

In the future, NFTs will be cheap and common, like a deck of playing cards. If you want to hear more about how NFTs resemble playing cards, run over to YouTube and watch today’s video.

Lockdowns and Suicides

A year ago, many governments implemented lockdowns as a way to control the spread of COVID-19. Since then, many have not only doubted their efficacy but have wondered if they caused more harm than good. One idea I have seen floating around is that lockdowns caused an increase in suicides.

Could we use econometrics to test this hypothesis? First, we need a model to generate a hypothesis.

The model behind lockdown-induced suicides is easy to formulate. The probability of dying by suicide is a function of mental health, and it’s possible that lockdowns deteriorated mental health by keeping people confined and restricting access to friends and family. One hypothesis this generates is that areas with more restrictions should have higher suicide rates.

So if we wanted to test for this, what’s the first piece of evidence we would look for? Before implementing some crazy empirical strategy that tries to find a causal effect, we should just look at the raw data. And the raw data do not look like they support the model: in the U.S. in 2020, deaths by suicide decreased 5.6%.

So we already know that we’re not going to find a convincing argument that lockdowns increased suicides. UNLESS…what if suicides were decreasing, and lockdowns prevented them from decreasing further? Again, the raw data do not support this: suicides in 2019 were up 7.5% from 2015.

There could still be a connection between lockdowns and suicide. And it may be worth pursuing an empirical study to explore the connection. However, looking at the raw data can help set expectations.