Bad education advice

It's the time of year where a terrible education suggestion circulates.

In the U.S., taxes are due April 18. Throughout the year almost everyone pays taxes, through sales tax at the store or income tax from the paycheck, but April 18 is the last day you have to settle if all of your taxes have been paid. In most cases, all of those taxes combined means the individual has overpaid, so one incentive to file your taxes is that you usually get money back.

But the tax-filing process is so complicated that an untrained taxpayer cannot file without worrying that she's committing tax fraud. There are way more things that you are supposed to include in your taxes that you probably don't. For example, did you know, "If you steal property, you must report its fair market value in your income in the year you steal it unless you return it to its rightful owner in the same year"? That's straight from the IRS guidelines on filing taxes. Hopefully this isn’t a problem for you, but it demonstrates that the tax code contains way more than you know.

This brings us to the terrible education suggestion.

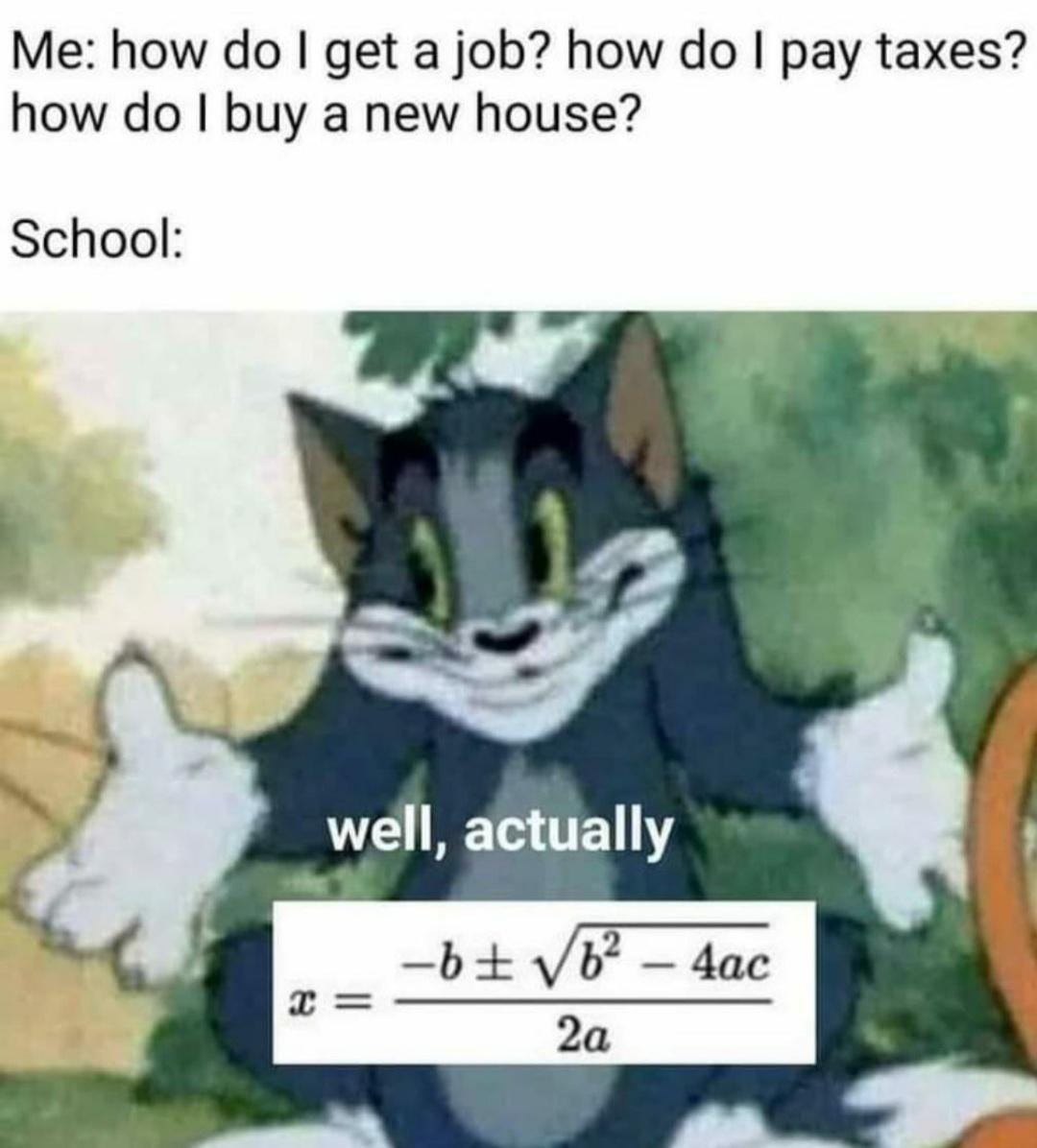

Every year, people from all around the internet post something like this meme.

The suggestion is that schools should teach something useful like paying taxes and instead they teach something esoteric like the quadratic equation.

Why is this a terrible suggestion?

So many reasons. First, it's commonly known that the reason taxes are so hard to file is that tax-filing software companies lobby the government to keep it complicated so people buy their services instead. The problem is not education.

Second, tax law is constantly changing. Even if tax brackets and rates don't change, legislation is always sneaking in new tax deductions or credits to nudge behavior. Anything you learn will become obsolete within a few years. In fact, I had a class when I was 12 where I learned how to write a check and balance my checkbook. How useful is that skill today?

It's this second point that gets me. We should be teaching students as many fundamental truths as possible. Fundamental truths represent not just the things we know today, but the things we expect to be still be true in 50 years.

Fundamental truths are the building blocks for innovation. Look at the quadratic equation. This esoteric formula that's pointless to teach students is what allowed Stuff Made Here to make a basketball hoop that automatically sinks your shot. When he learned the quadratic equation, he didn't know that he'd apply it like that one day. But when he wanted to build something no one had made before, he realized that he could rely on that fundamental truth.

Of course, not everything can be a building block because we're still learning. Physicists used to teach the plum pudding model of the atom, but now we know that's not how atoms are structured. Was it a waste to teach? No, of course not. Understanding the atom was important in 1904 when the model was proposed, and it's still important today. It will still be important in 50 years.

Even better, we can imagine how an understanding of the atom could change the world. Advances in material sciences are driving economic growth. In fact, Paul Romer points to this as one of the greatest places to look for growth.

To get some sense of how much scope there is for more such discoveries, we can calculate as follows. The periodic table contains about a hundred different types of atoms. If a recipe is simply an indication of whether an element is included or not, there will be 100 x 99 recipes like the one for bronze or steel that involve only two elements. For recipes that can have four elements, there are 100 x 99 x 98 x 97 recipes, which is more 94 million. With up to 5 elements, more than 9 billion. Mathematicians call this increase in the number of combinations “combinatorial explosion.”

Once you get to 10 elements, there are more recipes than seconds since the big bang created the universe. As you keep going, it becomes obvious that there have been two few people on earth and too little time since we showed up, for us to have tried more than a minuscule fraction of the all the possibilities.

Teaching kids how to file their taxes does not have that potential.

This is one reason why I'm interested in development economics. The other day I was talking to the father of one of my development students. He said the student was taking a marketing class at the same time and commented, "This is so dumb. All we're trying to do is get someone to click on an ad. Trying to solve world poverty is much more interesting."

I agree! And this is a wider problem. As pointed out in this article from 2014, "The brightest minds of a generation, the high test-scorers and mathematically inclined, have taken the knowledge acquired at our most august institutions and applied themselves to solving increasingly minor First World problems."

Filing taxes is a First World problem. Let's orient education towards solving real problems, then hire accountants to do the other stuff.

Note: Last week I published a video on development economics. Check it out on Market Power.